Representation Matters is a joint program of the Oliver Wyman Forum (OWF), Women Political Leaders, and the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law project, founded to research the crucial intersection of women’s political representation and legal equality. Latest research, conducted on behalf of the Representation Matters program partners, finds that countries that have more women in political offices typically pass more laws that increase women’s economic rights and opportunities, which can lead to greater female labor force participation and economic growth. The report offers short- and long-term recommendations as well as insights from female political leaders making a difference today.

Explore the Data

Click or search for a country to see a comprehensive view of women's political representation and legal equality, and explore the world map in each tab to see how variables have changed over time. Scroll below for the full report.

1970

Foreword

While the world has made progress toward gender equality, improvements have slowed significantly and even reversed in some areas, leaving the goal well out of reach. Women have two-thirds of the legal rights available to men,1 earn 80% of what men do,2 and have far fewer opportunities to run for public office.

But what if women were treated as equals? What if they had the same opportunities to study, work, and wield political power as their brothers, fathers, and sons?

Sound far-fetched? It’s not. Countries that have more women in political offices typically pass more laws that increase women’s economic rights and opportunities, which can lead to greater female labor force participation and economic growth, according to new research conducted for Representation Matters.3 Women Political Leaders (WPL) initiated the idea of launching Representation Matters, a joint program of WPL, the Oliver Wyman Forum (OWF), and the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law project (WBL), to research the crucial intersection of women’s political representation and legal equality.

This report comes at a critical time. Countries that are home to almost half the global population held elections in 20244 and women did not make broad-based gains, raising questions of whether these results are just a pause or possibly a setback. Greater representation can play a critical role in promoting equal opportunity for women and in providing a much-needed stimulus to world economic growth. Women’s leadership — in politics and business alike — can help more women fulfill their true potential and benefit their families and societies. According to the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law project, full female workforce participation could increase global GDP by nearly 20% and help reduce poverty.5

The report builds on 2023’s inaugural study and includes findings from an analysis of WBL data by University of Nebraska professor Alice Kang on behalf of the Representation Matters program partners. In this report, we offer short- and long-term recommendations as well as insights from female political leaders making a difference today. We want to thank Maria Rachel J. Arenas, MP, the House of Representatives, The Philippines (WPL Ambassador); Donna Dasko, Senator, Senate of Canada (WPL Community); Frances Fitzgerald, Member, G7 Gender Equality Advisory Council (GEAC) and Member of the European Parliament (2019- 2024) (WPL Community); Neema Lugangira, MP, Parliament of Tanzania (WPL Ambassador); Martha Tagle Martínez, Member of the Chamber of Deputies, Mexico (2018-2021) (WPL Community); and Millie Odhiambo, MP, National Assembly, Kenya (WPL Community) for their time and contributions to this report and the Representation Matters program.

For too long, the constrained political influence of women in many parts of the world has perpetuated a vicious cycle of limited legal rights and economic power. We hope our findings will inspire business, government, and individuals to act and turn that cycle into a virtuous one. We can turn what ifs into reality.

Silvana Koch-Mehrin

President and Founder of Women Political Leaders

Dominik Weh

Partner, Co-Head of the Government and Public Institutions Practice, Europe, Oliver Wyman

Norman V. Loayza

Director, Development Economics, Global Indicators Group, World Bank Group

“Equal representation is not a token gesture; it is the foundation of a functioning democracy. When women take their rightful place in political leadership, decisions are more (RIGOROUSLY) inclusive, and policies reflect the real needs of all citizens. As we look to the future, we must accelerate the pace of change. It is not just about counting the number of women in politics, but ensuring their voices are heard and acted on. This is how we will truly shape the course of global democracy. I am pleased that the WPL Representation Matters initiative has found committed partners in the Oliver Wyman Forum and the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law. This collaboration shows how data driven insights can open new pathways to achieving gender parity in politics, law, and economic opportunity.”

Dr. Obiageli "Oby" Ezekwesili

Founder and President of Human Capital Africa (HCA); Founder and Chair, SPPG/FixPolitics; Senior Economic Advisor, The Africa Economic Development Policy Initiative (AEDPI); Chair of the WPL Board

“In the face of sluggish global growth, high government debt, geopolitical tensions, and changing demographics, world leaders urgently need to find fresh sources of momentum. They need look no further than their female citizens. World Bank research shows that extending equal rights and opportunities to women could double the global growth rate and increase world GDP by 20%. It’s not only the right thing to do for women, and long overdue; it’s the smart thing to do for our societies.”

Ana Kreacic

Partner and Chief Knowledge Officer, Oliver Wyman, and Chief Operating Officer, Oliver Wyman Forum

“When women participate in political decision-making, they advocate for more gender-equal policies that benefit everyone. Unfortunately, discriminatory laws and inadequate policies hold women back from contributing their full potential. This report provides critical evidence and actionable recommendations for policymakers, the private sector, and advocates to close the gender gaps in political leadership, business, and the workforce.”

Tea Trumbic

Manager, Women, Business and the Law, World Bank Group

Executive Summary

The reasons for investing in and empowering women couldn’t be more pressing. Many of the forces that drove economic growth during the last three decades — disinflation, low capital costs, free trade, labor mobility, and geopolitical stability — have reversed or are in jeopardy, according to the Oliver Wyman Forum’s CEO Growth Agenda.6 That helps explain why the global economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic remains sluggish, with growth expected to hold steady for the first time in three years, at 2.6%, in 2024, and edge up to just 2.7% in 2025, according to the World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects7 report. People in one of every four developing economies were projected to be poorer at the end of 2024 than they were before the pandemic, and by 2026 countries that are home to more than 80% of the world’s population will still be growing more slowly than they were before the pandemic. Such weak growth is insufficient to make progress on the key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that global leaders have endorsed for ending extreme poverty and spreading prosperity around the world.

It is obvious that countries should make full use of all their resources to maximize their economic potential. What is less acknowledged is that women today represent one of the largest untapped assets and potential growth drivers. According to the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law 2024 report, closing the gender gap in employment rates between men and women could double the current world growth rate over the next decade, and boost global gross domestic product (GDP) by more than 20%. So when everyone is searching for growth, how do we enable change?

Make the barriers visible

Women across the world currently enjoy less than two-thirds of the legal rights available to men. Legal restrictions and the lack of legal protections are persistent barriers to fulfilling the fundamental right of everyone to be “born free and equal in dignity and rights,” as stated in the UN Declaration of Human Rights.8 The movement for equal rights has faced backlash in certain areas, driven in part by economic and geopolitical uncertainties. However, women’s limited rights restrict their ability to participate equally in the economy and contribute to growth, according to the WBL report. The gap is particularly notable in two areas that were added to the WBL index: Safety and Childcare, both critical for women to fully participate in the labor market. In addition, the reality that men disproportionately benefit from societal and legal systems is fundamentally unfair, unjustifiable, and unequivocally wrong.

On safety, for example, only 55% of the 190 economies covered by the report have comprehensive laws against domestic violence. And even where legislation exists, many economies lack the supportive frameworks, such as policies, institutions, and funding, to make rights a reality. In the area of center-based childcare, more than three-quarters of economies have laws covering childcare services, but fewer than half maintain a database of caregivers or provide families with financial support or tax breaks for childcare services. Remarkably, not a single country today grants women equal legal rights and, consequently, equal opportunities.

Create equal opportunities to political representation and legal equality

Men have traditionally dominated the political arena and agenda in most countries. Women need more seats at the political table to ensure that their voices are heard and their unique perspectives become part of future solutions. They can help bring attention to issues that disproportionately affect women and champion laws that oppose discrimination and make it easier for women to join the workforce or start a business.

Greater women’s representation in political decision-making bodies, including legislatures and executive cabinet positions, is correlated with improvements in women’s economic rights, according to new research conducted for Representation Matters. The analysis, conducted on behalf of the Representation Matters program partners by Alice Kang, a professor of political science at the University of Nebraska, and Sophia Stockham, a PhD candidate at the university, compares data on women’s political representation in 165 countries from 1970 to 2023 with country scores on the WBL index, which measures legal gender equality and assesses whether a country’s laws create an enabling environment for women to participate in the economy. The study finds that the relationship between political representation and women’s economic rights is positive and statistically significant, holding across regime types and country income levels.

Governments and political parties must play a leading role in creating equal opportunities for women to run for and hold office. Nearly half of countries surveyed by the United Nations operate some form of gender quotas that either apply to parties’ candidate lists or that set aside a certain percentage of seats for women. Other measures like anti-harassment laws can encourage more women to enter politics.

In addition to creating opportunities, governments should tackle discriminatory laws and regulatory barriers that prevent women from participating fully in the economy. Measures can include strengthening laws around women’s safety from violence and sexual harassment and expanding access to paid leave and childcare services. Governments should leverage data such as that provided by Women, Business and the Law and engage with leaders in civil society to identify legal and regulatory gaps and craft appropriate interventions.

Get serious about tackling bias against women leaders

Negative perceptions about women’s leadership potential are deeply rooted in most societies. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)9 finds that half the world’s people believe men make better leaders than women, and that view hasn’t budged in a decade. Indeed, people aged 18 to 34 exhibit more bias against women than older generations, according to the Reykjavík Index for Leadership,10 which measures perceptions about male and female leaders in Group of Seven countries.

Leaders in the public and private sectors and civil society all have work to do to help combat this bias and change perceptions. Governments can drive change with policy. UNDP’s latest Gender Social Norms Index report says policy measures that promote women’s equality in political participation and strengthen social protection and care systems can overcome gender biases that leave women spending up to six times as much time on domestic chores and care work as men in countries with the highest level of biased gender social norms.

The media should seek to portray women leaders as a norm rather than as exceptions and focus on their policies and achievements rather than their looks or lifestyle choices.

The private sector should wield its influence and example

Government by itself can’t assure that women have the same economic opportunities as men. The private sector serves as a vital engine of any thriving economy and has a big role to play in making gender equality a reality, both with its voice and its actions.

Enterprises can use their public platforms to express their support for increased women’s representation on a nonpartisan basis. They could consider tying their financial and other support of political parties to their stances on women’s participation in politics.

Private sector enterprises also can lead by example. Organizations can implement strong anti-discrimination and equal pay measures to lower barriers to women’s employment and set quotas for C-suite and senior leadership positions.

Our message is clear: Assuring equal rights and opportunities for women would deliver economic benefits to society at large. Women’s representation in political offices is crucial to fulfilling those goals. It’s time for the public and private sectors to work with civil society and commit to increasing women’s representation and securing equal rights.

The Economic Stakes Of Empowering Women

Women make up half of the global population. What if they participated in society and the economy on an equal footing with men? Unfortunately, they don’t. Women enjoy fewer legal rights than men, are less than two-thirds as likely as men to participate in the labor force, and earn 80% of what men do. And notwithstanding notable gains in some areas and geographies, progress on several important metrics has stalled for years, if not decades. In some cases, progress has reversed. The Taliban recently issued a ban on women’s voices and bare faces in public;11 Türkiye in 2021 withdrew from the Istanbul Convention, which provides a comprehensive framework for combatting gender-based violence;12 and women in some states of the United States of America have in recent years faced barriers to accessing various types of reproductive health care, following federal rule changes and court rulings around abortion.13

This inequality matters to everyone, not just women. According to the World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects report, the world economy has stabilized following the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it hasn’t regained its earlier vigor. Global growth is projected to run at a rate of 2.7% through 2026, below the 3.1% average of the decade before COVID-19.

Slow economic growth will have the greatest impact on the world’s poor. One in four developing economies were projected to be poorer by the end of 2024 than they were on the eve of the pandemic, according to the World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects report. Against this backdrop, the report projects that nearly half of developing economies will see their per capita income gap relative to advanced economies widen over the first half of this decade, the highest share since the 1990s. Conflict, limited access to financing, ongoing geopolitical tensions, and other factors are contributing to the slowdown.

The pressure of these overlapping crises, combined with tighter fiscal constraints on governments, risk overshadowing the goal of gender equality. By some measures, it could take more than 100 years at the current rate of progress for women to reach parity with men, according to the World Bank’s latest Gender Strategy.14

Promoting greater legal gender equality, providing access to economic opportunities, and closing the gender gap in male and female employment rates could raise global GDP by more than 20%, and double the global growth rate over the next decade, according to the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law report. Addressing these disparities is especially urgent now because many economies face severe labor shortages15 and the COVID-19 pandemic created setbacks for women in the labor market.16

The potential benefit is more pronounced in countries where the participation of women in the workforce is currently lower. For example, economic gains from closing gender employment gaps, measured in terms of long-run GDP per capita, are estimated to be 26% for Mexico, where the female labor force participation rate is 47%, compared with 3% for Canada, where the participation rate is 61%.17

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) finds similar potential in extending economic rights and opportunities to women. Closing gender gaps in labor force participation rates across 128 developing and emerging economies could boost their GDP by 23% on average, according to the Interim Guidance Note on Mainstreaming Gender at the IMF.18 “Now more than ever,” the report states, “it is imperative to include gender as part of the path for a stronger, more inclusive, and sustainable growth.”

Some countries are already making significant progress, typically led by female politicians. Sierra Leone, for example, has advanced women’s rights and increased its WBL index score to 93 in 2023 from 32 in 1970.19 Women leaders such as Manty Tarawalli and Dr. Isata Mahoi, the respective former and current Ministers of Gender and Children’s Affairs, have played an active role in driving and implementing legal reform.

Specifically, at the end of 2022, Sierra Leone passed the Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Act (GEWE Act), which aims to increase women’s representation in parliament to 30% and prohibits gender-based discrimination in access to financial services. The Female Caucus of Parliament in Sierra Leone was instrumental in reigniting efforts to pass the GEWE bill between 2018 and 2019.20

The caucus members not only advocated for the bill within parliament but also engaged with civil society organizations and grassroots communities to ensure broad-based support. In addition, the Female Caucus of Parliament provided legal counsel and logistical and technical support when drafting the GEWE Act and throughout the legislative process.21

Increasing women’s representation in positions of political power is a crucial factor in promoting gender equality and unlocking those economic gains: According to Kang’s analysis conducted on behalf of the Representation Matters program partners, women’s representation in legislatures and cabinet positions globally correlates to greater legal rights and protections for women that affect women’s opportunity to participate in the economy. This is in line with the findings of other scholars who have proposed that, in contexts of systemic gender inequality, the inclusion of women on decision-making bodies will influence a variety of outcomes, including policy adoption.22 Numerous qualitative and quantitative studies provide evidence that female officials substantively represent women’s interests23 and that women’s presence in legislatures and cabinet positions is connected with the adoption of policies that seek to improve women’s access to the economy and address women’s interests more broadly.24

Impact story

Millie Odhiambo – Kenya

MP, National Assembly, Kenya; WPL Community

MP, National Assembly, Kenya; WPL Community

Millie Odhiambo became interested at a young age in politics, but was told by many that it wasn’t something “good Christian girls did,” especially because her husband isn’t from Kenya and she isn’t a biological mother. Fortunately, others encouraged the human rights lawyer to run, and she has been a member of parliament since 2008, most recently appointed minority whip.

Odhiambo has earned a reputation as a strong advocate for girls and women, encouraging them to shed traditional views of what a “good woman” is and instead act boldly, as she has. “Good girls don’t succeed. Be a bad girl like me,” she tells young people. “I am a bad girl, and as a bad girl I’m here serving my fourth term,” she says.

While Kenya still hasn’t met its goal of women holding at least a third of seats in parliament, Odhiambo has seen significant changes in recent years as more women are elected. “Women who have come in, even in the affirmative action seats, are now also bringing bills that seek to empower women further,” says Odhiambo. One such bill would require the government to provide free sanitary napkins “because it has been documented that a lot of our girls drop out of school because of period shame, because they’re not able to afford sanitary towels.”

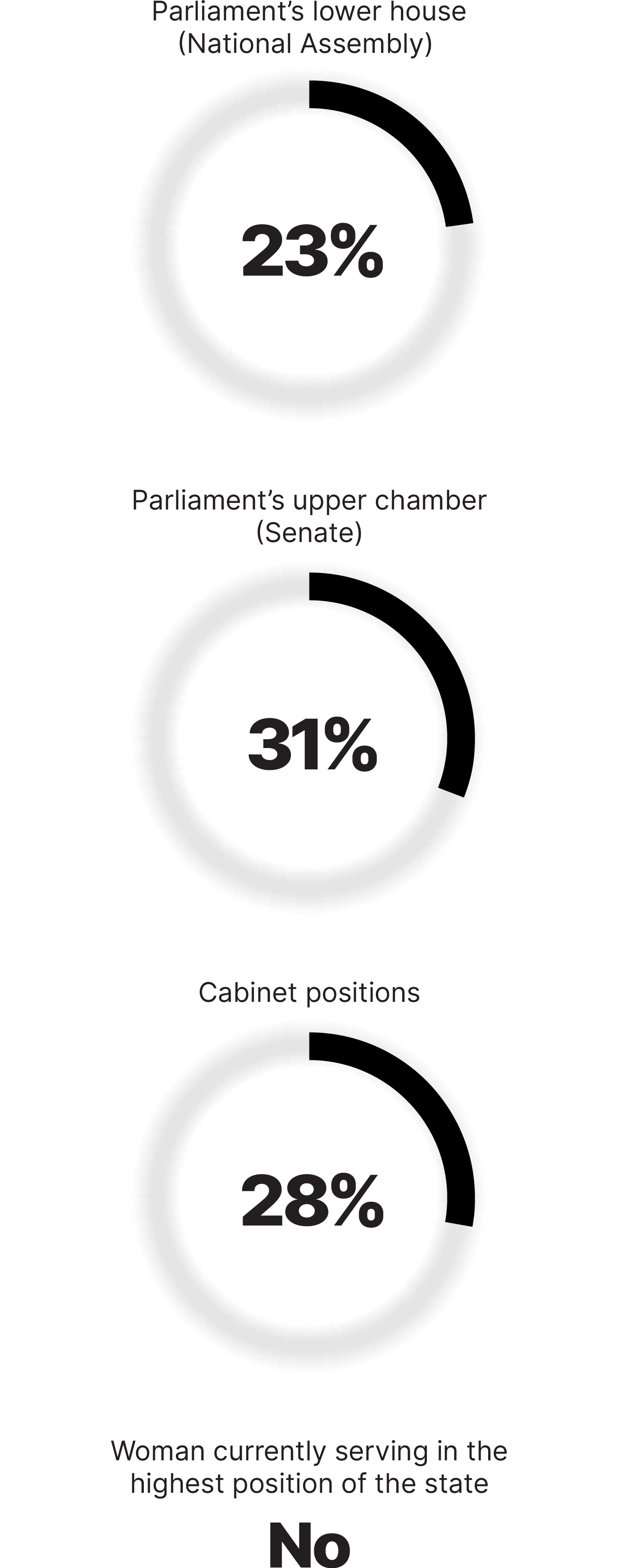

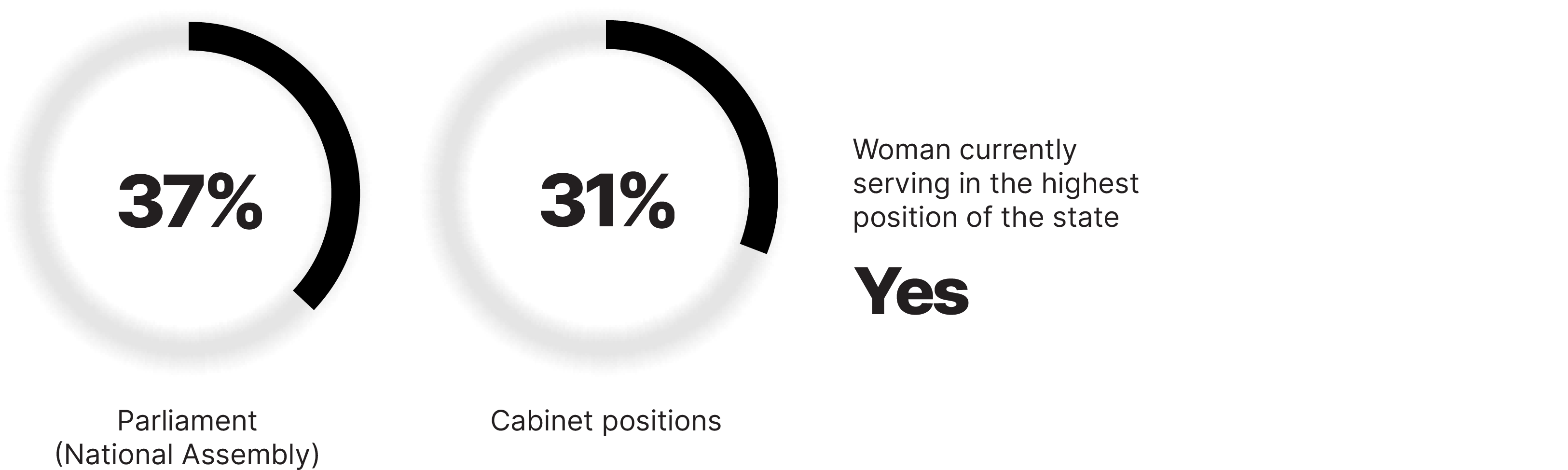

Women’s representation in Kenya25, 26

Impact story

Martha Tagle Martínez – Mexico

Member of the Chamber of Deputies, Mexico (2018–2021); WPL Community

Member of the Chamber of Deputies, Mexico (2018–2021); WPL Community

For former Mexican congressional deputy Martha Tagle Martínez, women’s power and democracy are two sides of the same coin.

The recent election of Claudia Sheinbaum as Mexico’s first woman president provides an opportunity to transform the country’s male-dominated political culture and govern with a different, broader set of priorities. “We believe that when a woman comes to power, she should not strip away her womanhood and what it means to live with inequalities,” Tagle Martínez says. “A woman president should come with the vision that we need more than just police and armed forces to guarantee the population’s safety. We also need infrastructure, cultural change.”

Tagle Martínez, who has been campaigning to extend access to abortion for nearly 20 years (it’s currently legal in less than half of Mexico’s 32 states), acknowledges that change won’t come overnight. But she is a firm believer in the power of women’s networks to provide support and champion change. “As we say around here, ‘My girlfriends save me.’”

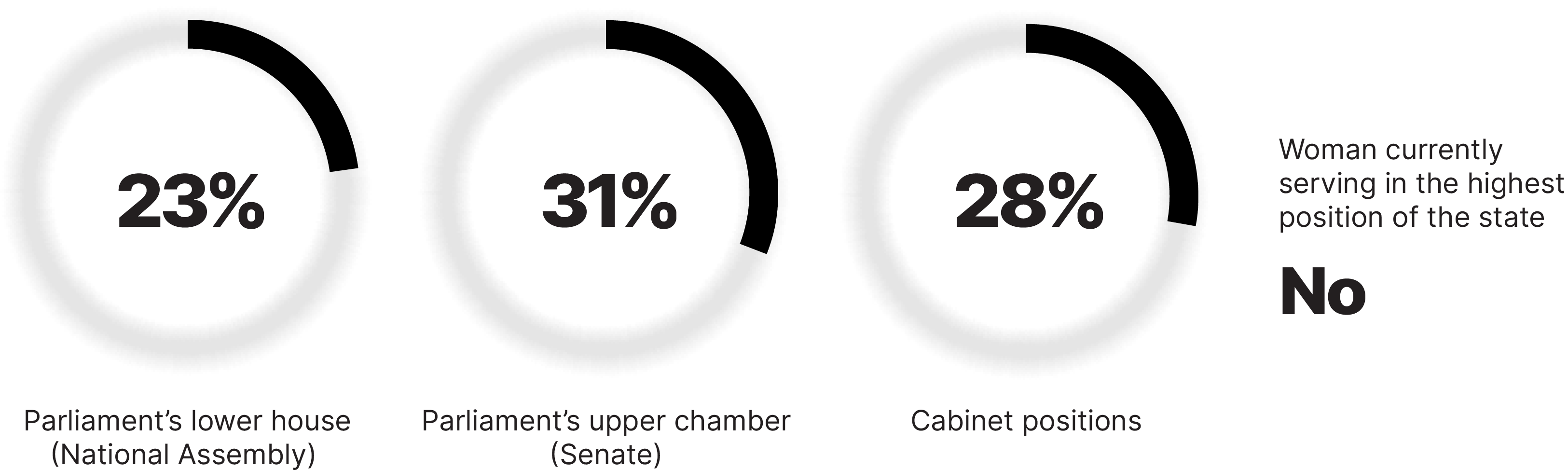

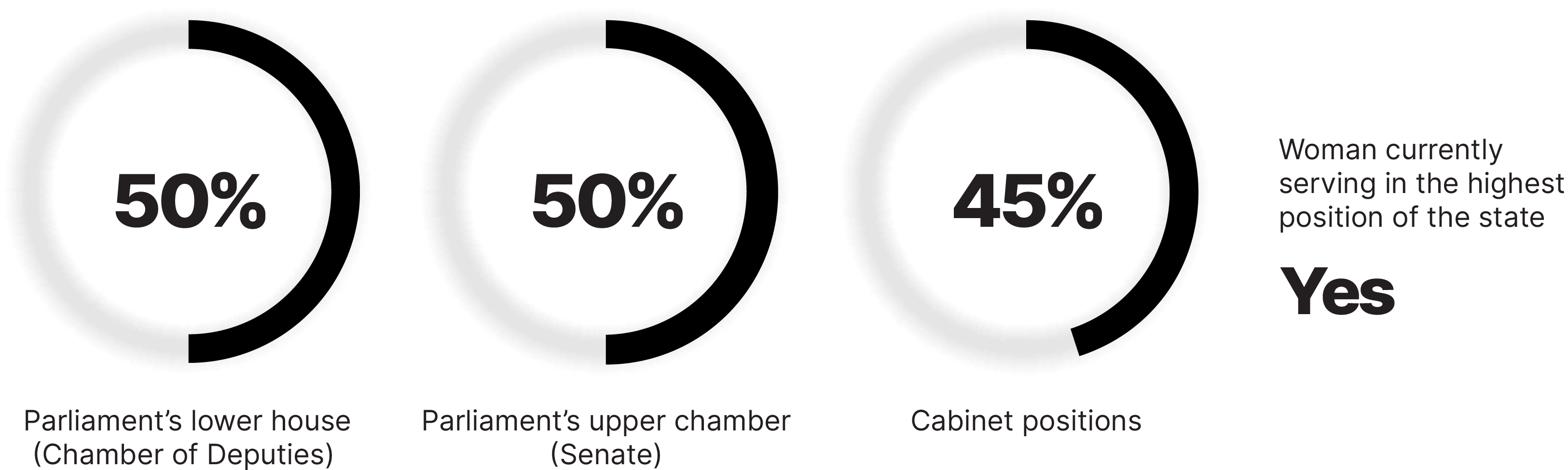

Women’s representation in Mexico27

Following June 2024 elections

The barriers to women’s full participation

Unleashing women’s economic potential is anything but guaranteed. They still face many barriers that impact their personal and work lives and prevent them from participating fully in the economy, notwithstanding the progress made in recent decades. Reasons for women’s underemployment and barriers to their participation in the economy are manifold and country-specific, and so are the most effective measures to address these gaps. That said, a common objective across countries should be the removal of legal barriers to increase women’s access to economic opportunities. Women enjoy less than two-thirds of the economic rights as men, according to the World Bank’s latest WBL index.

The index measures different aspects of the law that impact women and their participation in the economy, ranging from the ability to get a job or start a business to receiving equal pay for work of equal value and exercising rights over property and inheritances. The latest Women, Business and the Law report also examines laws and protections in two new dimensions: Safety, including legal protections against child marriage, femicide, and harassment in public spaces; and Childcare, including access to affordable and quality childcare. When all these factors are taken into account, no country provides equal opportunities for women.

Out of 10 measured dimensions, countries score worst on the new Safety indicator. Women have about a third (36%) of the legal protections they need from domestic violence, sexual harassment, child marriage, and femicide. Domestic violence severely affects many women’s lives and can decrease the number of women in the workforce, minimize their ability to acquire skills and gain an education, and have spillover effects on the next generations, reducing the potential of the future labor force. Access to quality care for children and adults could also improve outcomes for women, children, and the economy. Globally, women spend on average almost three times more of their day on unpaid care work compared to men,28 and over 40% of young children — or nearly 350 million — don’t have access to necessary childcare.29 As populations age, the burden will likely worsen as women provide most of the care for aging relatives and children. Enacting childcare laws could increase women’s labor force participation by 2% on average and by up to 4% five years after enactment, according to the World Bank.30

Additionally, many countries lack the implementation mechanisms that can turn rights into a reality. For example, while 98 (52%) of the 190 economies assessed by WBL have laws mandating equal pay for work of equal value, only 35 (18%) have adopted pay transparency measures or enforcement mechanisms to ensure the pay gap is closed in practice.

Impact story

Frances Fitzgerald – European Union

Member, G7 Gender Equality Advisory Council (GEAC); Member of the European Parliament (2019–2024); WPL Community

Member, G7 Gender Equality Advisory Council (GEAC); Member of the European Parliament (2019–2024); WPL Community

Addressing domestic violence is a priority for Irish politician Frances Fitzgerald, who served as a member of the European Parliament from 2019 until 2024 and pushed the EU directive to combat violence against women and domestic violence — a law that aims to prevent gender-based violence and protect victims, especially women.

“It was not an easy process to pass this directive, and there were a number of obstacles and hurdles that had to be faced and overcome, particularly when it came to the idea of including an offense of rape based on lack of consent,” says Fitzgerald.

Having a critical mass of women in the European Parliament and the European Commission made a crucial difference. “Having women in positions of power matters, and we must collectively work together, cross-party, to make that a reality,” she says.

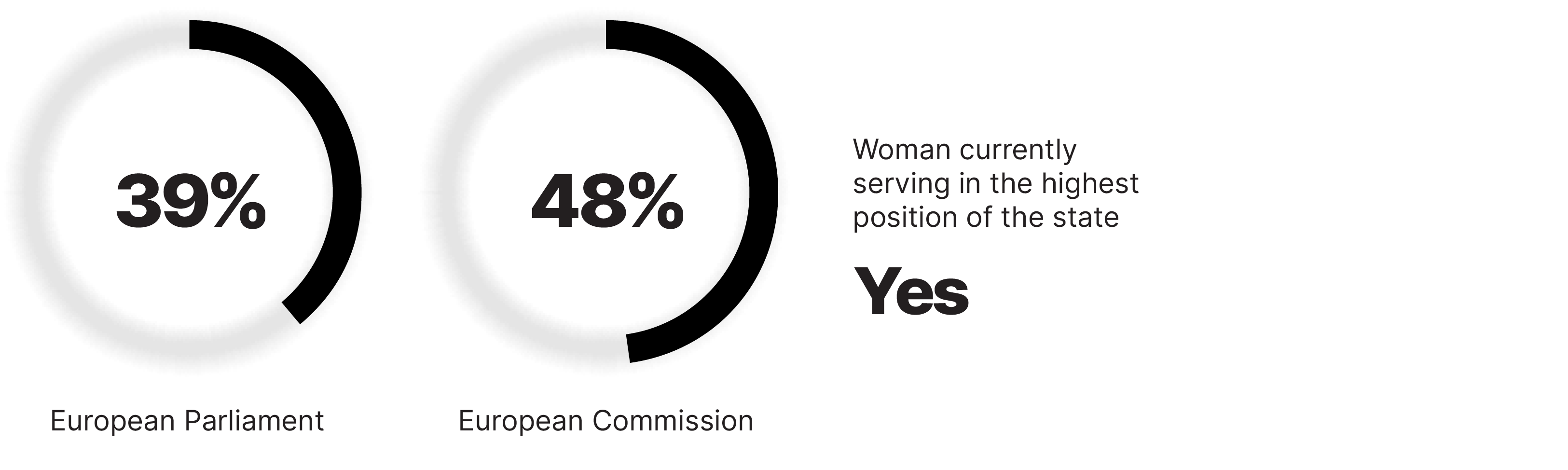

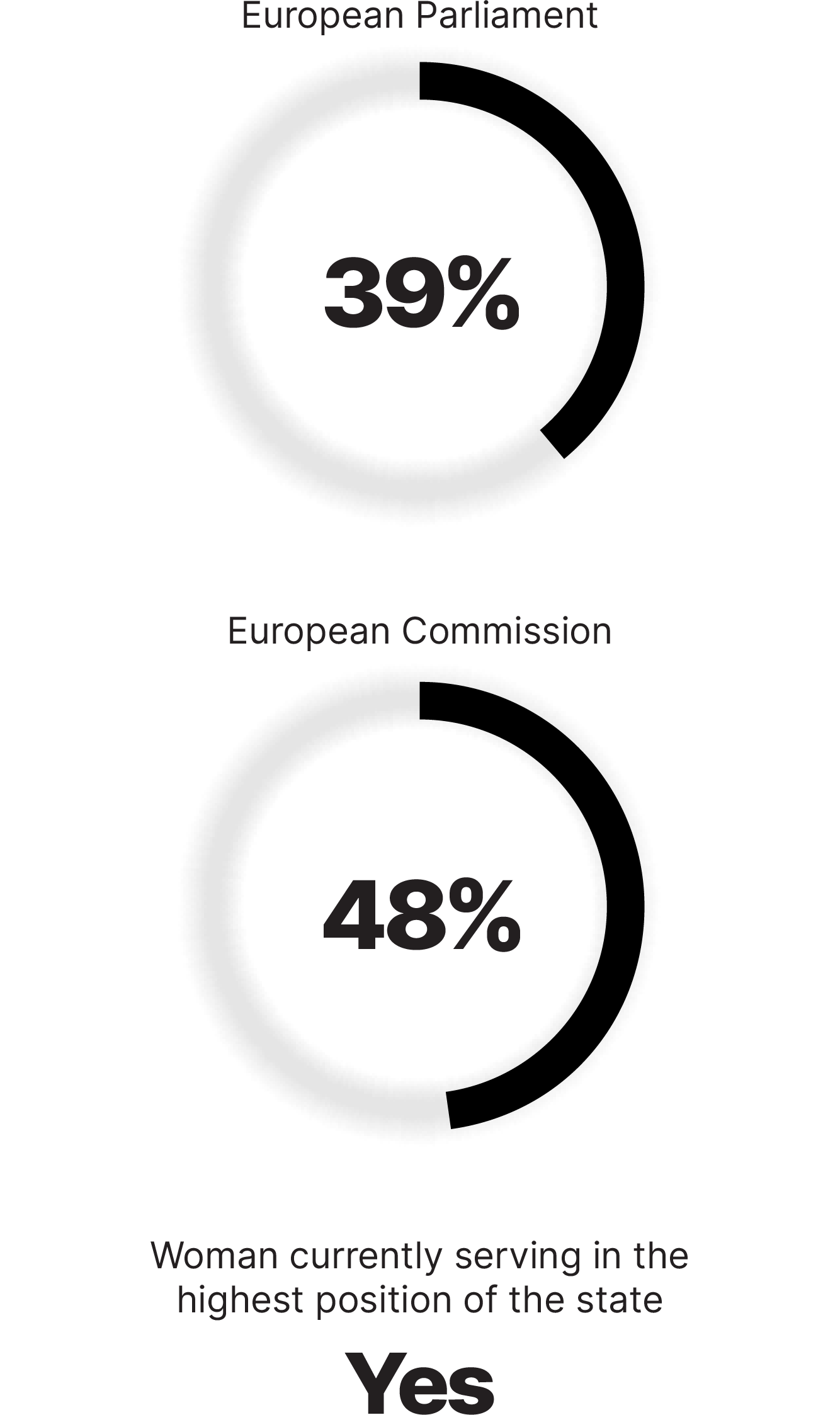

Women’s representation in the European Union31

Following July 2024 elections

The importance and state of women’s political representation and legal equality

Greater political representation for women is linked to tangible progress. Kang’s research on behalf of the Representation Matters program partners finds that increases in women’s representation in legislatures and cabinet positions is significantly and positively correlated with improvements in legal gender equality, as measured by the WBL index. The relationship holds regardless of a country’s income level and regime type.

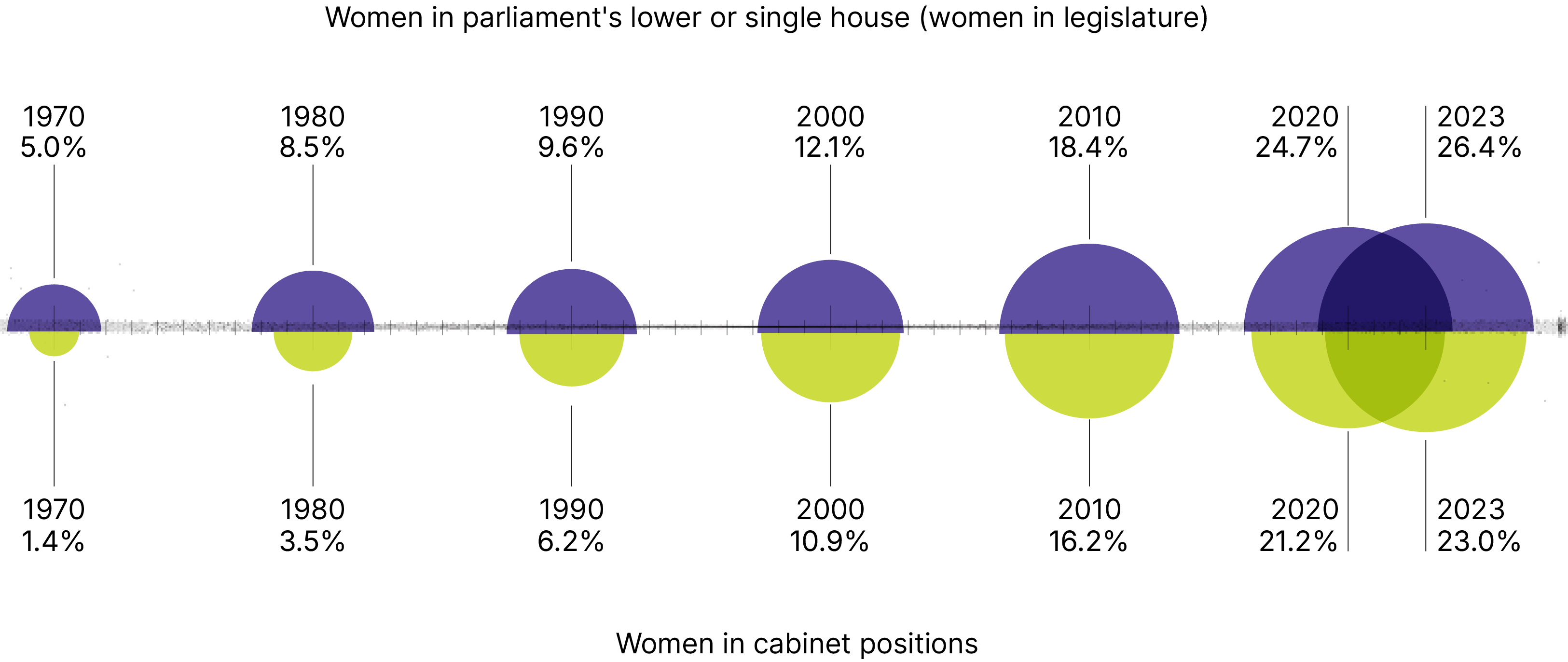

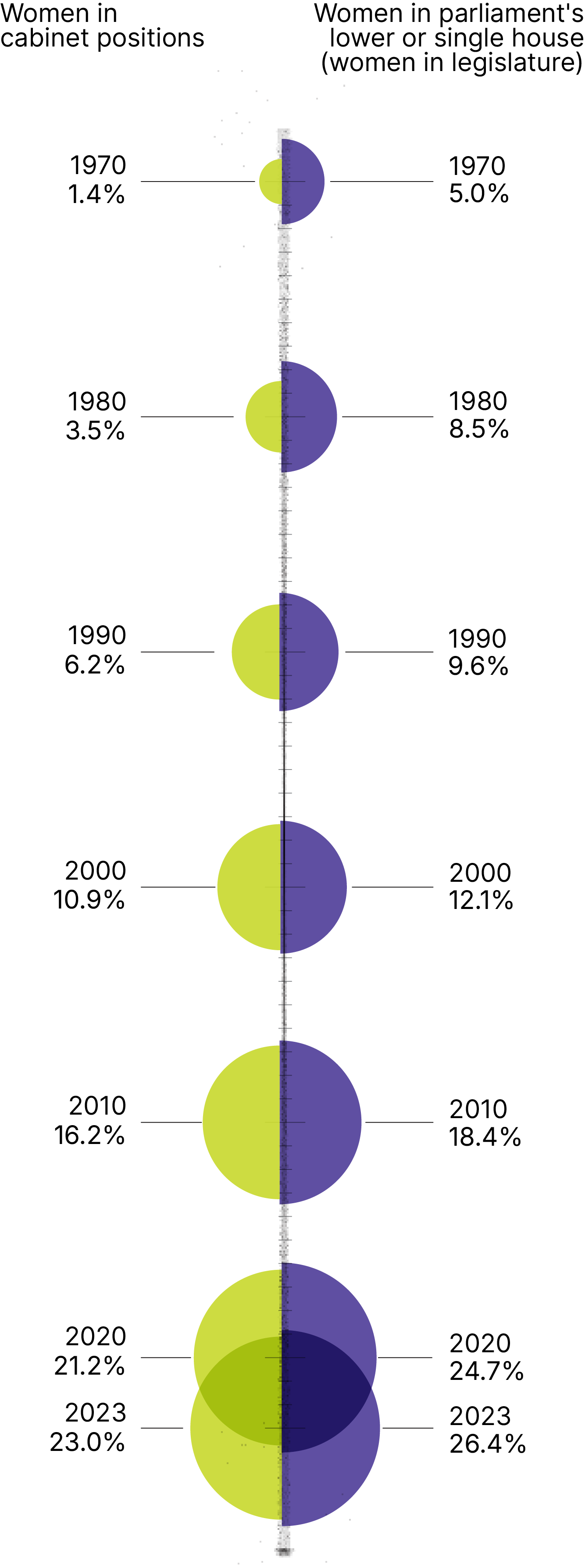

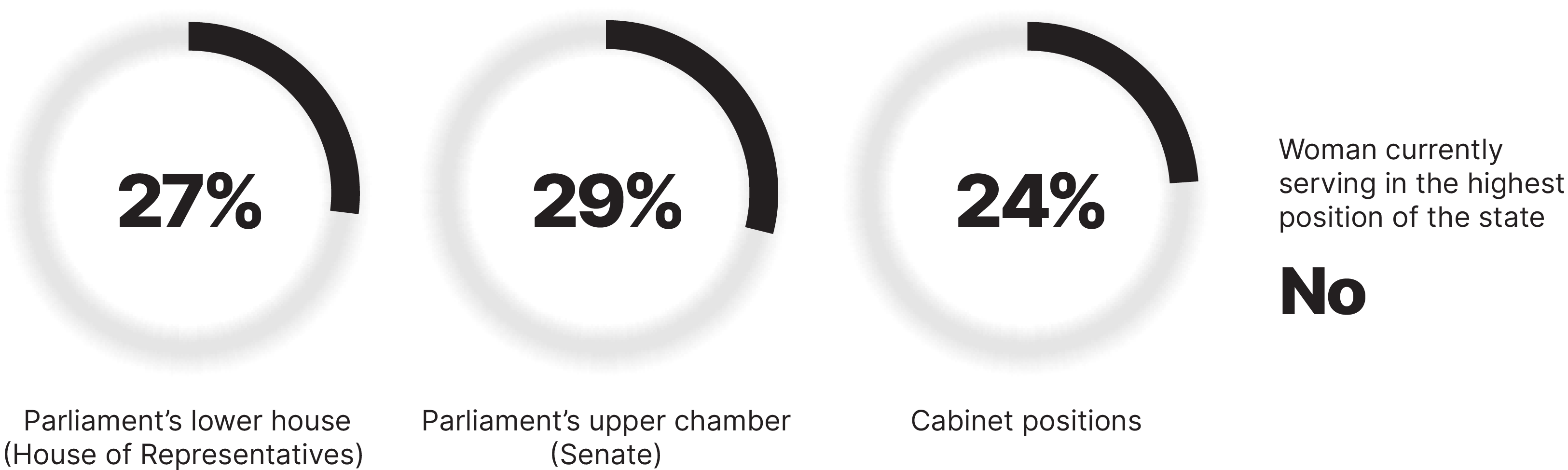

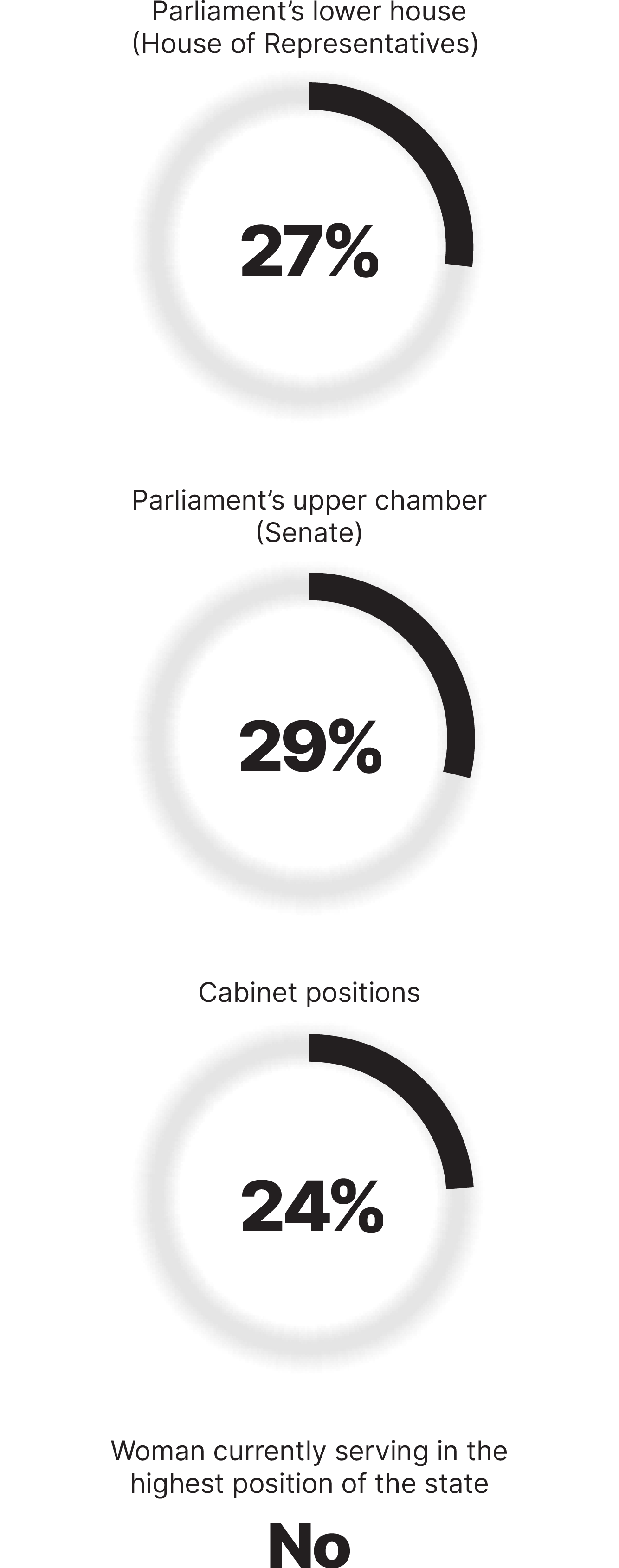

There’s one sticking point, though. Women still are significantly underrepresented in parliaments and governments globally, and progress has slowed. In 2023, women held just 26%32 of lower or single house parliamentary seats, on average, around the world, and 23%33 of cabinet positions. These figures are up by 20 percentage points and 22 points, respectively, over the past 50 years, and up by six and five percentage points, respectively, over the past 10 years. At the current rate of gains, it will take another four decades or more for women to achieve parity with men in political representation.

Only six countries (Andorra, Cuba, Nicaragua, Mexico, Rwanda, and the United Arab Emirates) have achieved political parity in the parliament’s lower house or unicameral legislature,34 and five (Australia, Bolivia, Canada, Mexico, and Zimbabwe) have parity in the parliament’s upper chamber.35 Eleven countries (Albania, Andorra, Belgium, Canada, Finland, Liechtenstein, Mozambique, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, and Spain) have half (or more) of their core cabinet positions held by a woman.36 Additionally, women serve in the highest position of the state (head of state and/or head of government)37 in 27 of the 193 countries. Only in 15 of the 27 countries does the office held by a woman have effective power.38

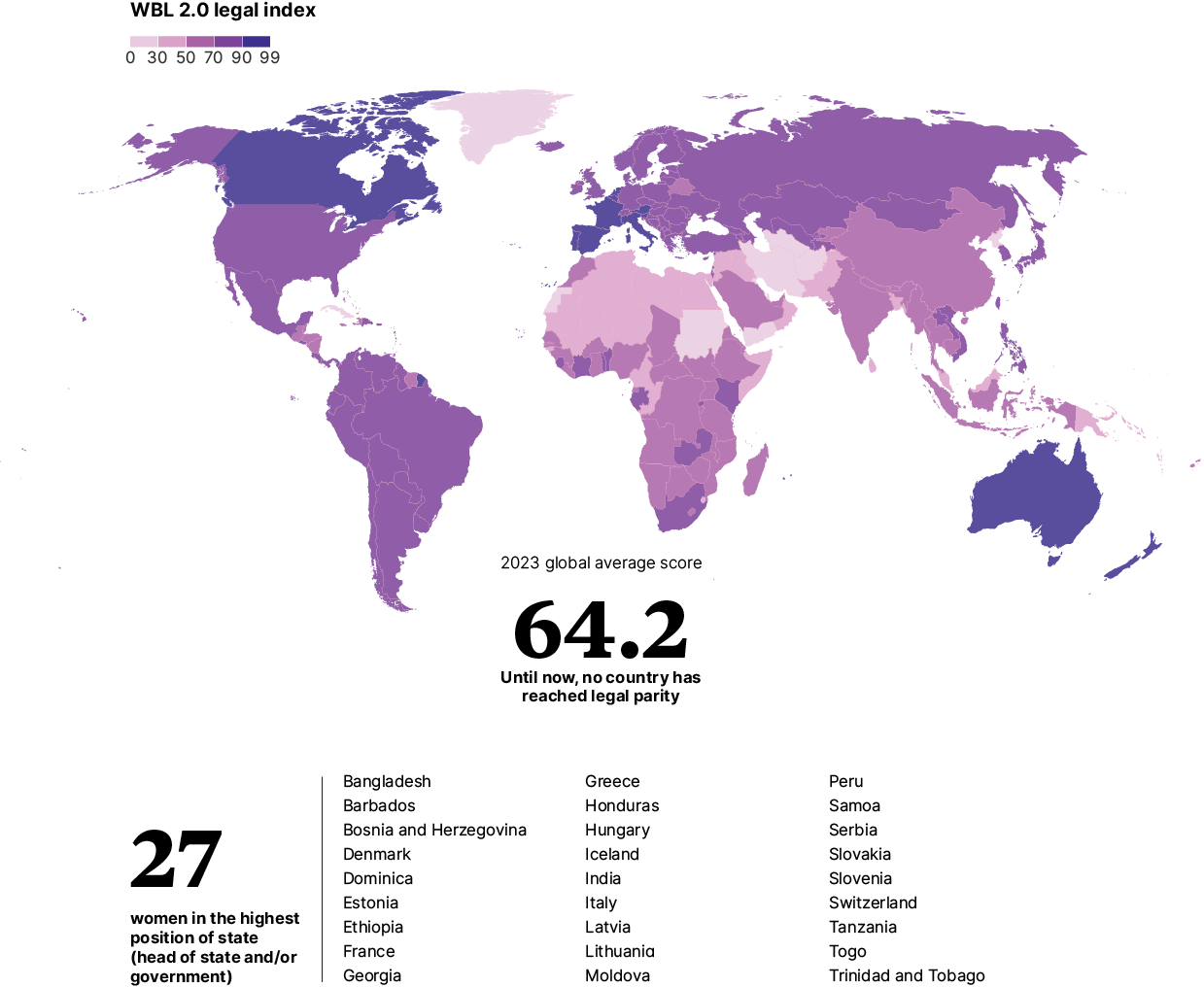

And while some countries have achieved gender parity in their government bodies, we see that, worldwide, no country has reached legal parity. Globally, the 2023 average score for the WBL 2.0 legal frameworks index was only 64 (out of 100).

Global state of women’s political representation and legal equality

(year-end 2023)39

Evolution of the global average per year, in percentage

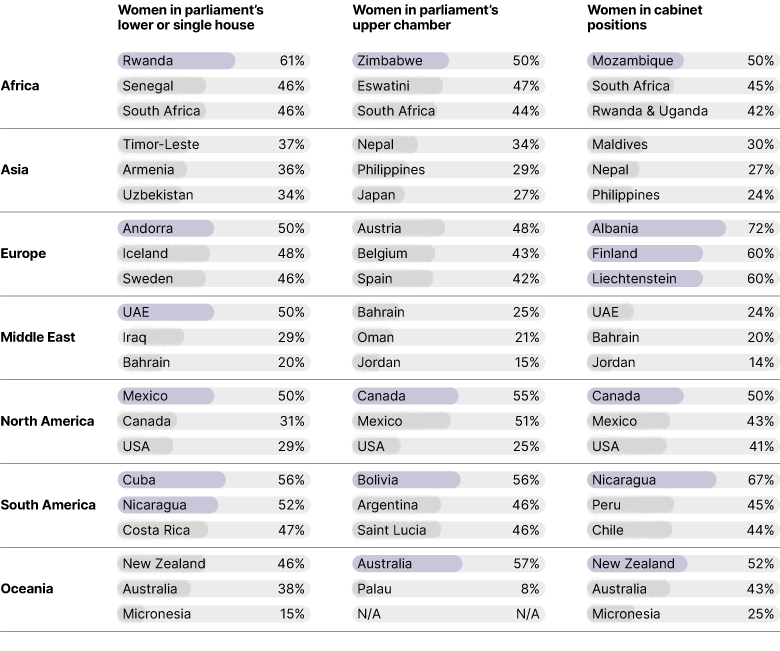

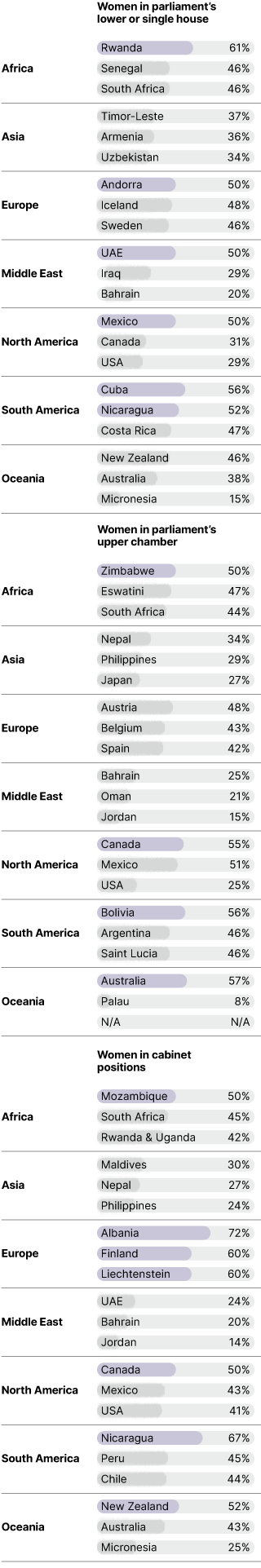

Top 3 countries in each region by share of women in government, in percentage

Impact story

Maria Rachel J. Arenas – The Philippines

MP, the House of Representatives, The Philippines; WPL Ambassador

MP, the House of Representatives, The Philippines; WPL Ambassador

Maria Rachel J. Arenas was first elected to the House of Representatives in 2007. She studied in the Philippines and the United States before returning home to learn more about politics. Running for office was challenging, but Arenas wasn’t intimidated, not even when a local mayor — a strong ally — was assassinated while he was standing beside her. “That didn’t stop us from showing people that we were not scared, that we were there to fight for the marginalized, for the vulnerable, to give them a better future,” says Arenas.

Many more women have been elected, and Arenas has seen considerable progress, including the passage of the Philippine Magna Carta of Women, a law that seeks to eliminate discrimination against women. “Since its enactment, we have seen a significant increase in women’s participation in leadership roles,” says Arenas.“There’s also now a balanced representation of women and men in local judiciaries and in local government.” Arenas says the newly elected women are having an impact on society. “These women often prioritize issues like gender equality, healthcare, education, and social welfare, reflecting their focus on inclusive policies. They also push for laws addressing women’s rights, such as anti-violence measures and reproductive health, alongside advocacy for climate action and youth empowerment. Their presence brings fresh perspectives, moving away from traditional politics and promoting more progressive, people-centered legislation.”

Women’s representation in the Philippines40

The super election year of 2024 presented an opportunity to increase women’s representation, but resulted in only modest improvements (see sidebar below entitled "Selection election results through year-end 2024"). The share of women in the legislatures of France, India, and Pakistan fell between one and four percentage points, as compared to the most recent prior elections held.

In contrast, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, South Korea, and the United Kingdom experienced gains of four, six, one, one, and seven percentage points, respectively, as compared to the most recent prior elections held. Mexico elected its first-ever female president, Claudia Sheinbaum.

Countries and societies have come a long way in recent decades, but the path to equal representation and opportunity remains far from complete.

Selected election results through year-end 202441

Results compared to outcome of each country’s most recent prior election

Why Women’s Representation Matters

It makes intuitive sense that having more women in positions of political power would be linked with more policies that advance the rights of girls and women, including access to greater economic opportunity. The new research by Kang on behalf of the Representation Matters program partners provides the latest empirical evidence of a significant correlation between women’s representation in positions of political power and changes in laws that address gender inequality in economic opportunities.54 The background paper prepared by Kang, including the study’s methodology, as well as the codebook and data set are accessible on the Oliver Wyman Forum Representation Matters landing page.

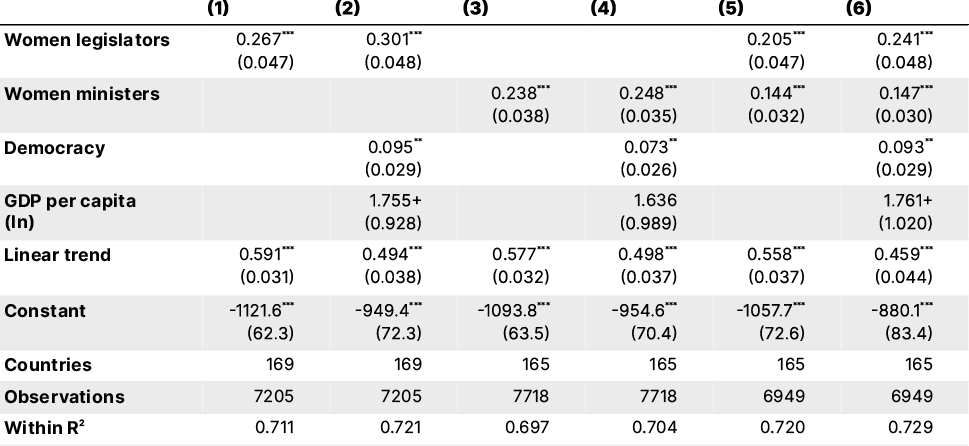

The study looked at data on the representation of women in the legislature,55 which in this report refers to the lower or single house in parliament, and cabinet positions56 across 165 countries from 1970 to 2023, and compared those figures with the countries’ scores on the World Bank’s WBL 1.0 index. This index measures laws and regulations on eight indicators that affect women’s access to economic opportunities (Mobility, Workplace, Pay, Marriage, Parenthood, Entrepreneurship, Assets, Pension). The analysis yields three key findings:

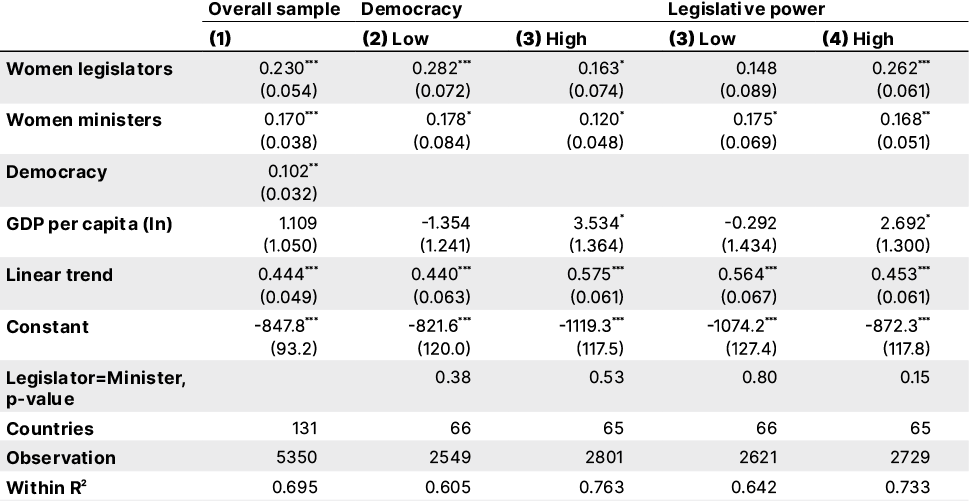

1. Women’s political representation is linked to an improvement in legal gender equality

The research finds a statistically significant correlation between increases in women’s political representation, both in legislative and in cabinet positions, and improvements in legal gender equality. This relationship is found to be statistically significant with p <.001, meaning there is a less than 0.1% probability that the observed results occurred by chance. The study updates and builds on earlier research by Nam Kyu Kim of Korea University,57 which we featured in our 2023 Representation Matters report and which showed a similar correlation between women’s political representation and legal rights. That report was based on data up to 2015. The new research includes nine additional countries using data through 2023. It shows that the relationship between representation and economic rights remains significant.

While it is important to note that the findings don’t prove a causal link between women’s representation and legal gender equality, they provide evidence of a link between the two. More specifically, the research correlated women’s representation with WBL index scores, with a three-year lag to account for the length of time it can take for legislative bills to be enacted into law — and the results show that increases in women’s representation are positively correlated with the adoption of more gender equal laws three years later.

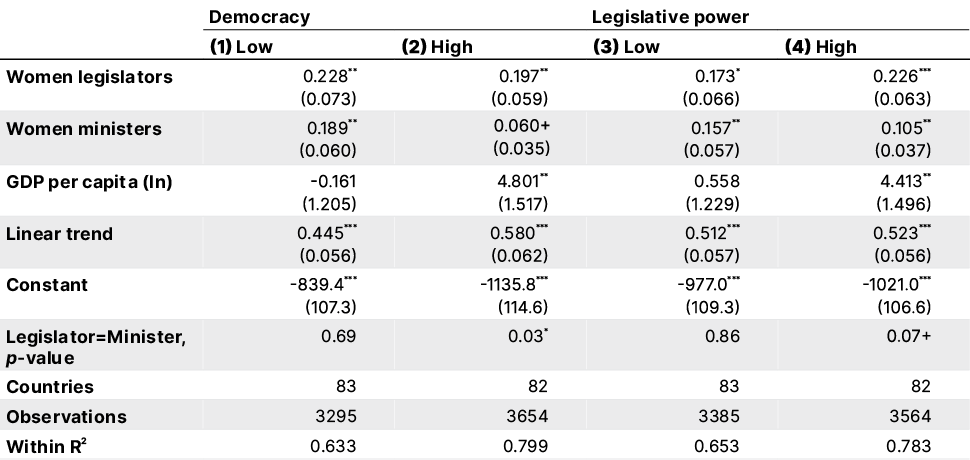

2. The relationship holds across various country contexts — and is strongest where a country’s legislature provides opportunities for women in office to present and pass meaningful laws, and to reform discriminatory ones

The correlation between representation and economic rights is robust even when controlling for socioeconomic factors such as a country’s wealth (measured by GDP per capita and oil income58), the regime type, or the political tilt of the largest party in the government. The relationship holds even when high-income OECD countries — which tend to have more gender equal laws (as measured by Women, Business and the Law) as well as higher levels of women’s representation — are removed from the analysis.

Change in the WBL index and in women’s representation over time

Relevance of a country’s level of democracy

Legislative and cabinet representation corresponds to improvements in legal gender equality across regime types, that is, across countries with a high level of democracy and those with lower levels of democracy.59 In the global analysis (including high-income OECD countries, N=165), in countries with higher levels of democracy, legislative representation has a stronger correlation with legal gender equality than cabinet representation. Legislative and cabinet representation have a similar relationship with legal gender equality in countries with lower levels of democracy. When limiting the analysis to non-high-income OECD countries (N=131), the study does not find a difference between the strength of the relationship between women’s legislative representation and women’s cabinet representation and legal gender equality across low democracies and high democracies.

Relevance of a country’s level of legislative power

Increases in women’s representation correspond with improvements in legal gender equality in countries with higher and lower levels of legislative power.60 However, how much power political leaders actually have matters to the relationship observed. In the global analysis (including high-income OECD countries, N=165), when the legislature has greater lawmaking powers, changes in women’s legislative representation have a stronger relationship with legal gender equality than do changes in women’s cabinet representation. Additionally, when the legislature’s lawmaking power is high, as a greater percentage of women hold legislative positions, policies that promote gender equality are more likely to be adopted than when legislative power is low. When limiting the analysis to middle- and low-income countries (excluding high-income OECD countries, N=131), it still appears that the institutional context is important. With this sample, similar to the global sample, when the legislature’s lawmaking power is high as a greater percentage of women hold legislative positions, policies that promote gender equality are more likely to be adopted, but not when legislative power is low.

Greater women’s representation in political positions corresponds with improvements in gender equality globally, even when controlling for socioeconomic factors and regime type. And the relevance of representation goes beyond mere numbers: The institutional context of each country plays a pivotal role. When a country’s legislative body wields greater lawmaking powers, women’s legislative representation corresponds more strongly with laws that affect women’s economic opportunity compared to when the legislative body has weaker lawmaking powers. That is, the relationship between women’s legislative representation and more gender equal laws is strongest where legislatures provide an enabling environment for all policymakers, including women, to present and pass meaningful laws, to remove legal barriers and to reform discriminatory laws.

3. Women’s political representation is linked to an increase in legal protections from gender-based violence

Based on a linear regression model, the research finds that increases in women’s legislative and cabinet representation is associated with an improvement in laws protecting women from sexual harassment in the workplace61 and domestic violence62 (N=165).63 In countries where women have greater political representation, there is a consistent and statistically significant correlation with the adoption of laws addressing gender-based violence.64

This finding is particularly important given the severe lack of legal instruments to address gender-based violence. The WBL 2.0 index, measured for the first time in the 2024 Women, Business and the Law report, shows that globally women have barely a third (36%) of the legal protections they need from domestic violence, sexual harassment, child marriage, and femicide. The new Safety indicator scores the lowest out of all 10 measured indicators. This gap has important consequences for women: The World Health Organization65 estimates that, globally, about one in three women have been subjected to physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime, and 27% of women aged 15 to 49 who have been in a relationship report that they have been subjected to some form of physical and/ or sexual violence by their intimate partner. Comprehensive legal frameworks, along with prevention measures and services for victims, are urgently needed to address this pervasive issue.

Additionally, better protections from gender- based violence can lead to positive economic outcomes, by enabling more women to enter the workforce and participate in the economy. The economic impact of gender-based violence is significant. The European Institute for Gender Equality estimates that the cost of gender- based violence across the EU is €366 billion a year.66 Further, a study from the IMF on sub‑Saharan Africa suggests that when the rate of violence against women and girls increases by 1 percentage point, economic activities reduce by up to 9%.67 Moreover, another study from the IMF estimates that eliminating child marriage would significantly improve economic growth — if child marriage were ended today, long-term annual per capita real GDP growth in emerging and developing countries would increase by 1%.68

Passing anti-harassment laws also helps women in the political arena. A study69 conducted in 2017 and 2018 in four countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Honduras, Tanzania, and Tunisia) revealed that 55% of women interviewed had experienced at least one form of violence while carrying out their political party functions, the largest share suffering psychological violence (48%), followed by economic violence (36%), sexual violence (23%), threats and coercion (23%), and physical violence (20%). An IPU study70 conducted in 2018 among 45 European countries with 123 members of parliament and parliamentary staff revealed that 85% of respondents had suffered psychological violence, 47% had received death, rape, or beating threats, 58% had been a target of online sexist attacks on social networks, 68% had been a target of comments relating to their physical appearance or gender stereotypes, 25% had suffered sexual violence, and 15% had suffered physical violence.

Such aggressions take a toll. In a survey of UK Members of Parliament by the Fawcett Society, 93% of women MPs said online abuse impacts negatively their feelings about the job, compared with 76% of men, and 73% of women agreed they “do not use social media to speak up on certain issues because of the abusive environment online,” compared with 51% of men.71

We note that the analysis is exploratory and focused on specific areas of gender-based violence.72 There is scope to use the new Safety indicator to explore more in depth the relationship between women’s political representation and laws addressing gender-based violence.

Impact story

Neema Lugangira – Tanzania

MP, Parliament of Tanzania; WPL Ambassador

MP, Parliament of Tanzania; WPL Ambassador

Female officials are leaving office because of vicious attacks on social media. Neema Lugangira, a member of Tanzania’s Parliament, hasn’t let harassment discourage her from using the technology to communicate with constituents.

“I told myself that if I stop using social media, I’m giving them a win. Instead, I decided to use my experience to address this issue and work with the African Parliamentary Network. And I’m grateful that a lot of other organizations — the UN Population Fund (UNPF), UN Women, UNESCO — are all addressing the issue of online abuse.”

She says it’s crucial for women to get elected because they inspire others and introduce legislation that positively impacts women. “For example, when President Samia Suluhu Hassan was vice president, one of her first priorities was improving access to water to make sure that women stop carrying buckets on their heads,” says Lugangira. “Why? Because she knew as a woman that having to go fetch water removes a woman from access to economic activities, removes a girl from schoolwork, and paves the way for gender-based violence.”

Women’s representation in Tanzania73

Paths To Achieving Political Parity And Gender Equality

This report makes clear that increasing the number and influence of women in politics is not only the right thing to do but also the smart thing to do for governments and society.

While we have not proven causality yet, the significant positive correlation between women’s representation and legal equality indicates that a greater number of women in politics can move the needle and have a measurable impact on the enabling environment of laws and policy mechanisms that gives women greater access to economic opportunities worldwide. In turn, more women in the workforce can provide one of the biggest boosts to global economic activity, which is urgently needed to expand prosperity and achieve our shared sustainable development goals. This is why we believe it is essential to increase women’s representation in political bodies to drive change and ultimately achieve legal equality between men and women.

Despite significant progress by governments and society toward greater political and economic equality over the past half-century, women are still a long way from full equality. Gender bias persists in much of the world and in many areas of human activity. Our call for action has one ambition: Increase women’s representation in our political bodies, especially those with the power to make laws and impact policy.

Equal rights for women are an issue that concerns all of society, not just women. We all have a role to play in changing attitudes and extending opportunity to women. Governments, political parties, and the private sector and civil society can contribute significantly to increasing women’s political representation.

Here’s how:

- 1. Governments and political parties must create equal opportunities for women to run for, win, and hold office

- 2. Governments should reform discriminatory laws and remove regulatory barriers, such as those tracked by Women, Business and the Law, that keep women from having equal opportunities

- 3. Governments and the private sector should work to counter biases, especially those against women as capable leaders

- 4. The private sector should leverage its influence to advance women’s political representation while setting an example by fostering gender equality in the workplace

1. Governments and political parties must create equal opportunities for women to run for, win, and hold office

Most countries have political systems that were designed by men and for men. Women did not win the right to vote in major industrial countries until the early part of the 20th century, and they didn’t enter politics in significant numbers until the past 50 to 60 years. They held less than 7% of legislative seats globally in 197474 and less than 2% of cabinet positions.75 Today, those percentages stand at just 26% of legislative seats76 and just 23% of ministerial positions77 — progress, to be sure, but well short of women’s share of the world’s population.

In part, the representation gap reflects an unlevel playing field. The top five factors that are perceived by survey respondents to help people become successful government leaders are (1) opportunities to make key contributions, (2) opportunities to make key decisions, (3) experienced mentors, (4) merit-based leadership promotions, and (5) influential sponsors, according to OWF’s Global Consumer Sentiment Survey.78 Although roughly half of respondents deemed all factors to be equally accessible by both men and women, the remainder said the factors were more easily accessed by men. Additionally, men typically have an easier time securing financial support for political campaigns due to a number of factors, such as incumbency advantages; strategic party behaviors; fewer economic barriers;79 a gender gap in resources, which makes it easier for men to fund their own campaigns and contribute to others;80 and general gender discrimination in societies.81

Governments and political parties need to close that gap and create equal opportunities for women. Proven mechanisms exist for doing just that, and political bodies can decide what methods suit their particular political context and culture. Some of the options include:

Gender quotas

Ninety-four of the 193 countries surveyed by the United Nations employ some form of quota,82 with 18 reserving a certain percentage of seats for women and 76 setting quotas for candidates. France, for instance, requires the number of men and women on parties’ candidate lists for the National Assembly to differ by no more than 2%.

Incentives and penalties

Legislation can link party funding to gender parity or impose penalties on parties that failed to achieve gender goals. As noted by Rainbow et al., in Ireland, for example, political parties face financial penalties for not meeting a quota, while in South Korea they receive financial incentives for successfully achieving it.

Term limits

Enforcing term limits for political officeholders prevents long-term incumbency, which often benefits men based on historical gender balances. The introduction of strict term limits in the Philippines in 1987 led to a significant increase in the number of women running and winning in mayoral elections. However, it is worth noting that this effect was largely confined to dynastic women, meaning those related to outgoing incumbents.83

Anti-harassment laws

Passing and enforcing anti-harassment laws to protect women from gender-based violence would have several benefits, including for women who want to be or are active in the political arena. Several countries have implemented these types of laws. The Canadian Human Rights Act protects individuals from discrimination based on sex and gender, including harassment, while Tanzania has recognized gender-based violence as an electoral offense.84

Quality care services

Providing access to quality care not only increases women’s economic participation, it also enables them to run for and hold political office. Care work disproportionately falls on women, and the global population is projected to age significantly further in the next decades, by almost 20 years in China, almost six years in the United States, and almost nine years globally in the next 50 years.85 The care burden will worsen as the global population continues to age, making it difficult for women to maintain paid jobs and political positions.

This is not an exhaustive list, and countries can (and many do) employ more than one mechanism. The essential thing is for leaders to acknowledge that you can’t change the status quo without legal reform.

Impact story

Donna Dasko – Canada

Senator, Senate of Canada; WPL Community

Senator, Senate of Canada; WPL Community

Senator Donna Dasko believes greater female representation is making a difference in Canada. Legislators tried in 1988 and 2005 to pass childcare legislation but didn’t succeed. “We finally passed a national childcare policy during COVID, and I’m convinced it was because we have our first female finance minister, Chrystia Freeland,” says Dasko, who was appointed in 2018 to the Canadian Senate by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. “It shows very clearly that when you have women in these positions, you can get legislation passed that is really helpful for women.”

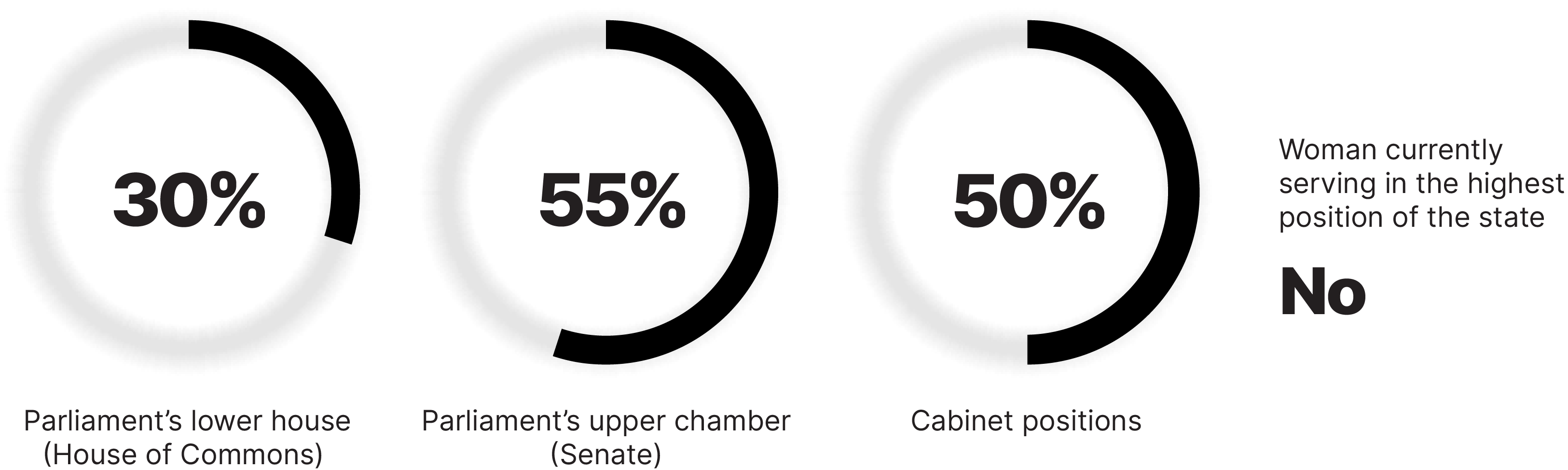

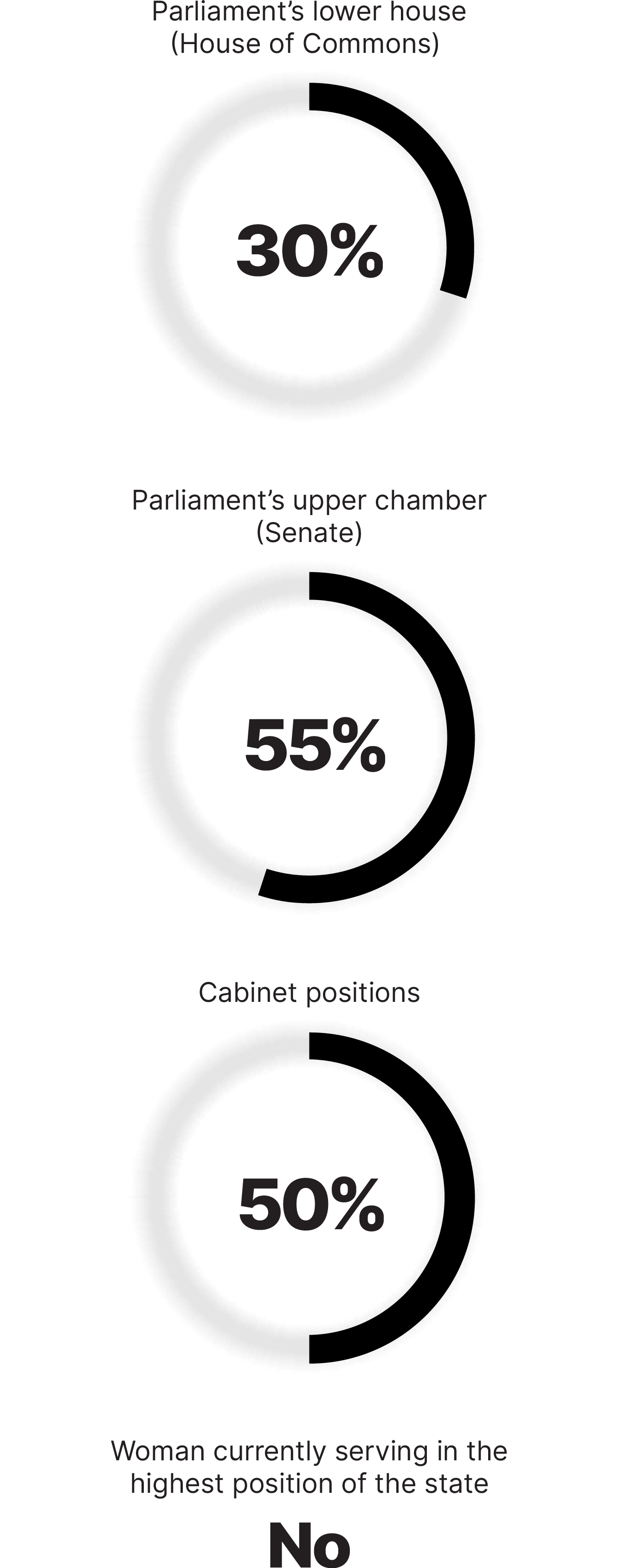

More needs to get done, says Dasko, who cofounded Equal Voice, a nonpartisan organization that seeks to get more women elected in Canada. The Canadian Senate currently is gender- equal because Trudeau appointed a fair number of women, but the House of Commons — the elected chamber — has a share of only 30% women.

“Our voices should be represented in our parliaments in proportion to our population,” says Dasko. “It’s actually a principle of democracy, and democracy is in trouble in the world. This is one of the ways to strengthen it.”

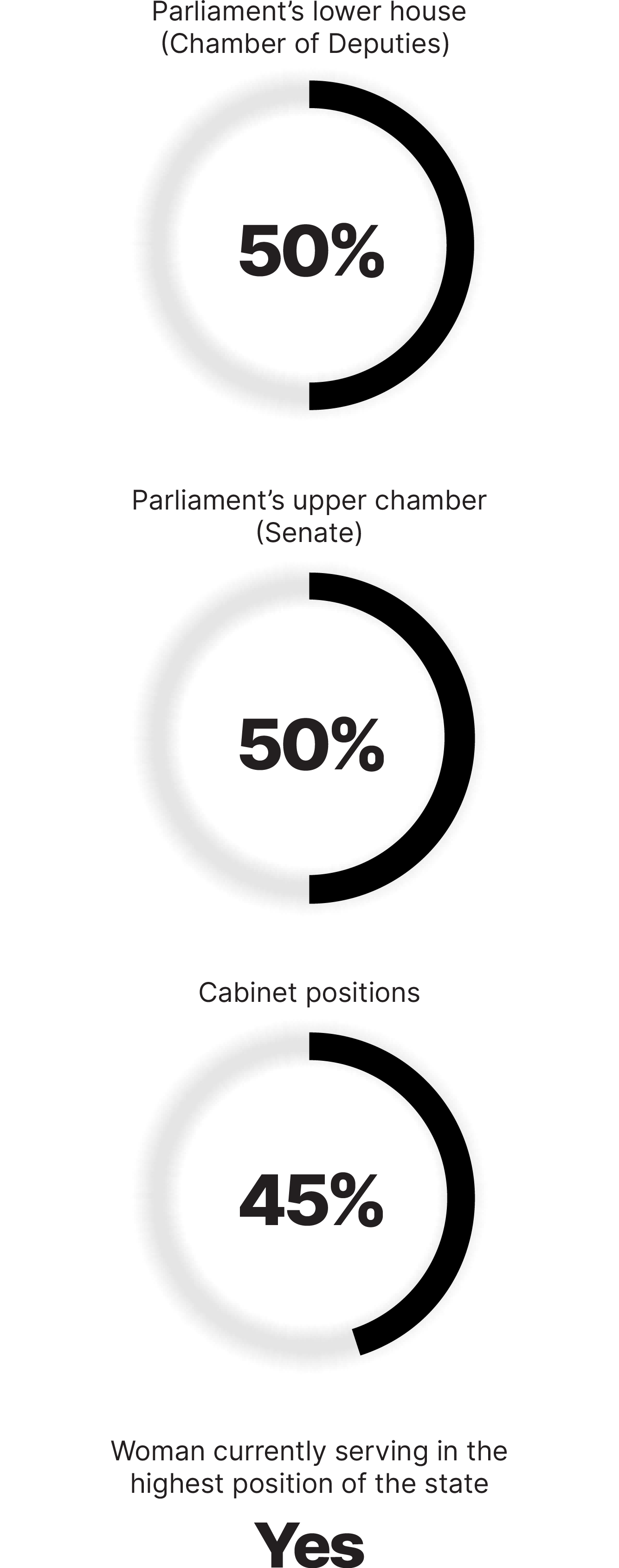

Women’s representation in Canada86

For the House of Commons, as of June 2024

2. Governments should reform discriminatory laws and remove regulatory barriers, such as those tracked by Women, Business and the Law, that keep women from having equal opportunities

Governments must accelerate efforts to reform laws and enact public policies that ensure equal economic opportunities for women and establish frameworks for the effective implementation of gender equal laws. This includes improving laws related to women’s safety from violence and sexual harassment, expanding access to paid leave and childcare services, and increasing opportunities for women to join and remain in the labor market, as well as to start and run their own businesses.

The long-term benefits of boosting women’s economic participation should motivate governments and development partners to fund such reforms, which often create environments that drive further progress across the areas measured by Women, Business and the Law.87

In order to pursue comprehensive and effective legal reforms, governments should:

Leverage data for evidence-based policymaking

Governments should leverage comprehensive data, such as that provided by Women, Business and the Law, to identify gaps and prioritize reforms. By integrating robust data analysis into policy development, they can craft targeted interventions that effectively advance equal economic opportunities for women.

Engage with civil society

Governments can engage in regular consultations with civil society and gender experts in their countries to identify areas for intervention to dismantle legal and regulatory barriers for women.

Invest in gender-sensitive training

By targeting policymakers, parliamentarians, and government officials, gender-sensitive training on the importance of gender equality and how to use data and evidence for policymaking can help sustain long-term progress in ensuring equal opportunities for women.

3. Governments and the private sector should work to counter bias and promote the perception of women as capable leaders

Gender bias has deep roots in most societies and needs to be overcome to enable women to take on more political leadership roles. Leaders in the public and private sectors and civil society all have a role to play here. They can work together and, in their realms, encourage and ensure gender equality.

Consider that the United Nations Development Programme’s Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI) finds that nine out of 10 men and women hold biases against women,88 that 49% of the world’s people believe men make better political leaders than women, and that countries with greater bias in gender social norms have a smaller percentage of women in parliament. Equally significant, the index finds no reduction in bias during the past decade (see sidebar below entitled “United Nations Development Programme’s Gender Social Norms Index”).

The Reykjavík Index for Leadership, which measures the extent to which men and women in G7 countries are viewed equally in terms of their suitability for leadership positions, has not changed significantly in the past six years. The index, which grades attitudes on a scale of zero to 100, where a score of 100 would indicate men and women are viewed as equally suitable to lead, stands at only 70 across the G7. Worryingly, the index finds that people aged 18 to 34 are more biased against women than older generations, a finding that, if sustained, could potentially reverse gains toward gender equality.

When it comes to how media shapes perceptions, it is important to note that studies find that women politicians receive more media coverage focusing on their physical appearance than men, and also receive more family-related personal coverage.89 This is troublesome as voters generally respond similarly to most media messages about women and men candidates, while those focusing on traits, appearance, or family tend to be more harmful to women.90 Another study finds that the higher the level of media sexism, the lower the share of women candidates for parliament.91 A path forward could be establishing a charter across media to commit to avoiding gender-stereotyped portrayals of female politicians and candidates.

Altering societal perceptions is vital for the election of women to public office. The likelihood of women seeking and retaining political positions diminishes if they anticipate a lack of acceptance or recognition compared to their male peers, coupled with the possibility of facing harsher judgment. Moreover, the efficacy of women in office is at risk if pervasive negative gender stereotypes impede their political campaigns and the execution of their initiatives upon election.

Some of the options to address the gender bias are:

Education

Combatting perception biases within educational systems is essential, particularly among men and younger generations, who, according to research from the GSNI and Reykjavík Index for Leadership, exhibit the most biases. Furthermore, education that empowers women and fosters their autonomy, encouraging them to forge their own paths, can also contribute to a shift in societal attitudes, as highlighted in the latest GSNI report.

Policymaking

Governments and legislatures can shift perceptions with policy. The latest GSNI report says that policy measures that promote women’s equality in political participation and strengthen social protection and care systems can overcome gender biases that leave women spending up to six times as much time on domestic chores and care work as men in countries with the highest level of biased gender social norms. It’s instructive that the countries that score highest on the 2023- 24 Reykjavík Index, including Iceland (89) and Finland and the Netherlands (each at 82), have a sustained public policy agenda focused on gender equality that includes measures to support equal pay for work of equal value, parental leave, and equitable board representation.

Messaging and media

The media has an important role to play in changing perceptions. Media outlets should work to normalize women in positions of leadership. This can be achieved by intentionally treating male and female leaders equally, when it comes to coverage and specifically how they are presented and the type of questions they receive. It is also important to highlight key leadership traits, which are perceived to be common across genders by respondents, as the OWF GCSS showed.

United Nations Development Programme’s Gender Social Norms Index

The Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI) reveals that nine out of 10 men and women hold fundamental biases against women and that nearly half the world’s people (49%) believe that men make better political leaders than women do, and 43% believe that men make better business executives than women do. The GSNI covers 85% of the global population and quantifies biases against women by capturing people’s attitudes on women’s roles along four key dimensions. Each dimension is characterized by one or two indicators:

Political

“Women having the same rights as men is essential for democracy”

(scale 0–10; bias: 0–7; no bias: 8– 10)

“Men make better political leaders than women do”

(bias: “strongly agree” and “agree”; no bias: “strongly disagree” and “disagree”)

Educational

“University is more important for men than for women”

(bias: “strongly agree” and “agree”; no bias: “strongly disagree” and “disagree”)

Economic

“Men should have more right to a job than women”

(bias: “agree”; no bias: “neither” and “disagree”)

“Men make better business executives than women” (bias: “strongly agree” and “agree”; no bias: “strongly disagree” and “disagree”)

Physical Integrity

“Proxy for intimate partner violence (it is justifiable for a man to beat his wife)”

(scale 1–10, bias: 2– 10; no bias: 1)

“Proxy for reproductive rights (abortion is never justifiable)”

(scale 1–10, bias: 1; no bias: 2–10)

The index shows that biased gender social norms are widespread worldwide, across continents, income levels, and cultures — making them a global issue:

“Almost 90 percent of people have at least one bias”

“Even in countries with the least gender bias, more than a quarter of people have at least one bias” (New Zealand has the highest share of people with no bias, but still almost 27% hold at least one bias)

“Biases are prevalent among both men and women — suggesting that these biases are deeply embedded in society, reflecting widely shared social norms” (the smallest gap being in the dimension of “physical integrity” where 76.2% of men hold biases versus 73.4% of women; and the largest gap being in the dimension of “economic” where 64.7% of men hold biases versus 54.5% of women)

The GSNI proposes a comprehensive framework for transformative change, comprising two key blocks of action. The framework:

Aims to shape gender-sensitive policy interventions and institutional reforms through investment in gender-responsive institutions in public administration at the national and local levels, creating insurance systems for women through social protection and care systems and enhanced control over assets; and encouraging innovation in the form of innovative interventions.

Focuses on the significant role of the social context in shaping attitudes and “changing gender social norms through education that strengthens agency and encourages women to shape their own future, recognition that acknowledges women’s rights and respect for their identities and representation that amplifies women’s power and voice.”

4. The private sector should leverage its influence to advance women’s political representation while setting an example by fostering gender equality in the workplace

Women’s representation and access to economic opportunities are not solely the result of government policies. The private sector plays an equally important role in driving progress and creating a virtuous cycle throughout society. For example, private sector entities can leverage their influence to advocate for greater women’s representation in politics, using their own public platforms to underscore the importance of gender diversity in these settings and express their strong support for women’s inclusion. Additional actions may include:

Investing in women’s political endeavors

Firms can tie financial, campaign, and other forms of support to women’s representation in political parties.

Engaging directly with governments

Businesses can raise the issue of female representation with government representatives and collaborate on finding actionable solutions to enhance women’s participation in politics.

Amplifying advocacy through corporate platforms

Companies can use their corporate communications and media channels to publicly support increased women’s representation, maintaining a nonpartisan stance while driving awareness and change.

Promoting data-driven strategies

By collecting, analyzing, and publishing sex- disaggregated data — for example, on salaries, workforce composition by grades and promotion rates — the private sector can help identify targeted economic and policy measures that promote gender equality, providing a foundation for informed decision-making and advocacy.

Equally important is the role of private sector enterprises in advancing equal opportunity within their own organizations. These efforts complement stronger legal frameworks established by governments. Organizations can lead by example by voluntarily adopting higher standards and going beyond legal requirements to foster more inclusive workplaces. Some actions that private sector employers can take include:

Breaking down barriers to women’s employment

Implementing robust anti-discrimination and anti-harassment internal policies, adopting and enforcing equal pay and pay transparency measures, and establishing mentorship and sponsorship programs that cultivate a strong pipeline of female leaders at every level.

Driving cultural change

Encouraging a shift in workplace culture and norms by offering flexible work arrangements, such as flexible hours and remote work, extending paid paternity leave periods and encouraging fathers to effectively take them, and providing childcare services and accommodations for working mothers, such as nursing rooms.

These initiatives contribute to a more equitable distribution of caregiving responsibilities, which currently fall disproportionately on women.

Promoting gender parity and women’s leadership

Implementing strategies to ensure gender parity and increase women’s participation in leadership and decision-making roles within the organization. Consider setting specific targets for C-suite positions, internal working groups and task forces, and senior leadership positions. These strategies can serve as good practices for other organizations to emulate.

This report is just the beginning, a glimpse into the economic opportunity for all people through the transformative power of women’s political representation. The research shows that representation matters in advancing women, society, and the economy.

About The Report

Appendix

Appendix 1

Acknowledgments

This report builds on work done by other institutions that generously provided their data for further analysis to produce the insights presented here.

In particular, we want to acknowledge and express our gratitude to the following:

- Alice Kang and Sophia Stockham of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, whose research and insights on behalf of the Representation Matters program partners are the academic foundation of our report

- Nam Kyu Kim of Korea University, who provided invaluable insights into his work

- Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and UN Women, which provided annual quantitative data on women in national parliaments, ministerial positions, and leader of country and leader of government positions

- The authors of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) database and the authors of the WhoGov database, specifically Jacob Nyrup, who provided the historic and annually updated database on a variety of data on global governments, including on women’s representation in the legislature and cabinet positions

We want to thank the female political leaders making a difference today for their time and contribution to this report. All interviews have been organized through Women Political Leaders:

- Maria Rachel J. Arenas, MP, the House of Representatives, The Philippines; WPL Ambassador

- Donna Dasko, Senator, Senate of Canada; WPL Community

- Frances Fitzgerald, Member, G7 Gender Equality Advisory Council (GEAC); Member of the European Parliament (2019-2024); WPL Community

- Neema Lugangira, MP, Parliament of Tanzania; WPL Ambassador

- Martha Tagle Martínez, Member of the Chamber of Deputies, Mexico (2018-2021); WPL Community

- Millie Odhiambo, MP, National Assembly, Kenya; WPL Community

We would also like to present the full Representation Matters team from Women Political Leaders, the Oliver Wyman Forum, and the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law, which has worked relentlessly on this report and the program’s initiatives:

Steering Committee Members

- Silvana Koch-Mehrin, President and Founder, Women Political Leaders

- Ana Kreacic, Partner and Chief Knowledge Officer, Oliver Wyman, and Chief Operating Officer, Oliver Wyman Forum

- Dominik Weh, Partner, Co-Head of the Government and Public Institutions Practice, Europe, Oliver Wyman

- Tea Trumbic, Manager of the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law

Program Management

- Carolin Schlinkert, Associate, Oliver Wyman

Program Team & Contributors

- Sam Fenwick-Smith, Director of Partnerships, Women Political Leaders

- George Gyedu, Head of Project Management Office, Women Political Leaders

- Angela Lowe, Senior Advisor, Women Political Leaders

- Paola Aguirre, Research Analyst, Oliver Wyman

- Tom Buerkle, Editor, Oliver Wyman Forum

- Frances Ferguson, Partner, Corporate and Institutional Banking & Private Capital Practices, Oliver Wyman

- Maggie Lavoie, Senior Consultant, Oliver Wyman

- Jilian Mincer, Editorial Director, Oliver Wyman Forum

- Roianne Nedd, Global Director of Inclusion and Diversity, Oliver Wyman

- Mattias Sundell, Creative Project Manager, Oliver Wyman

- Adrien Slimani, Art Director, Oliver Wyman Forum

- Jerushalem Dalí Velasco Jasso, Web Developer, Oliver Wyman

- Moisés Pérez, Web Designer, Oliver Wyman

- Alexis Koumjian Cheney, Analyst, Women, Business and the Law, The World Bank

- Emilia Galiano, Senior Private Sector Development Specialist, Women, Business and the Law, The World Bank

- Natalia Mazoni Silva Martins, Private Sector Specialist, Women, Business and the Law, The World Bank

- Ana Maria Tribin Uribe, Senior Economist, Women, Business and the Law, The World Bank

- Hikaru Yamagishi, Economist, Women, Business and the Law, The World Bank

Appendix 2

Method

The key findings of this report are based on a study conducted by Alice J. Kang of the University of Nebraska and Sophia Stockham, a PhD candidate at the university, on behalf of the Representation Matters program partners.92 The study leverages data from 165 countries and covers 1970 to 2023. The background paper prepared by Kang, including the study’s methodology, as well as the codebook and data set are accessible on the Oliver Wyman Forum Representation Matters landing page.

This report includes multiple measures and data sources to provide as complete a picture as possible. In line with WPL’s guidelines, we report findings only for countries that are members of the United Nations.

We acknowledge that the data used for the study only looks at two genders. Data for other gender identities in this context is not available. We used the best data currently available. We acknowledge that the data will change as a result of the 2024 elections and other factors. We look forward to updating our findings with the latest data available to us in a next iteration of the study.

Dependent and independent variables

Dependent variable: Measure of legal equality in economic opportunities

Background paper: The main dependent variable is the extent to which a country’s laws and policies promote women’s access to economic opportunities. The measure for this variable is the WBL’s 1.0 index, which covers 1970 to 2023, and contains a number of corrections to the version of the WBL index that Kim used in his study. The index is scaled from 0 to 100, with 100 indicating that men and women have equal rights and opportunities in all the areas measured. The WBL 1.0 index combines scores on laws in eight areas: Assets, Entrepreneurship, Marriage, Mobility, Parenthood, Pay, Pension, and Workplace Protection. The authors created a preliminary ninth sub-indicator on Violence, in this Representation Matters report referred to as the “preliminary measure of laws protecting women from sexual harassment in the workplace and domestic violence,” to assess the relationship between women’s representation and legislation that addresses gender-based violence in the economy. Specifically, the authors use answers to two questions from the workplace questionnaire, “Is there legislation on sexual harassment in employment?” and “Are there criminal penalties or civil remedies for sexual harassment in employment?,” and responses to one question regarding marriage, “Is there legislation specifically addressing domestic violence?” In results reported in the study, the authors use the Violence index as a dependent variable.

Representation Matters report: In this report, the authors additionally reference and present the latest WBL 2.0 legal index, available for 2023, which includes for the first time two additional sub-indicators: Safety and Childcare.

Independent variables: Measures for women’s political representation

Background paper: The central independent variables are women’s representation in the legislature and women’s representation in the cabinet. Women legislators is the percentage of women in the lower house or unicameral legislature.93 Women ministers is the percentage of women in core cabinet positions.94

Representation Matters report: We also include data sources from IPU Parline (IPU), UN Women, and the latest available dataset from WhoGov to provide as complete a picture as possible for the status as of year-end 2023. For women legislators in the lower house or unicameral legislature — in this report also referred to as the lower or single house in parliament — we are adding data for 22 countries from IPU for the lower or single house as of January 1, 2024. For women ministers — in this report also referred to as women in cabinet positions — we are adding data for 24 countries from UN Women as of January 1, 2024. UN Women defines total ministers as “women and men Cabinet members who head Ministries. Heads of Government were also included where they held ministerial portfolios.” The dataset WhoGov, as included in Kang’s study, defines core members of the cabinet as “cabinet ministers, prime ministers, presidents, vice presidents, vice prime ministers, members of the politburo and members of a military junta as core positions.” This number excludes unoccupied positions, positions held by the same person, and posts that are not considered core positions. For this present report we are including the WhoGov data available through 2023, which was published end July 2024, when the study was already completed. This dataset includes data for 169 countries in 2023.

Methodology and hypothesis tests

To examine the relationship between changes in women’s representation and changes in legal gender equality of economic opportunity, the authors created a time-series cross-national database. The database’s period of coverage is 1970 to 2023, subject to data availability. The unit of analysis is the country-year. If a country was sovereign prior to 1970, it enters the dataset in 1970. For countries that gained independence after 1970, they enter the dataset in their year of independence. In the study, the authors limit the sample to countries that were member states of the UN as of December 31, 2023. The database includes up to 169 countries. For more information regarding country-year inclusion, please see the study’s codebook, published on the Oliver Wyman Forum Representation Matters landing page.

The study tests two main hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

As women’s representation in the legislature and cabinet increases, legal gender equality in economic opportunities improves.

Hypothesis 2

The relationship between women’s legislative representation and legal gender equality is stronger than the relationship between women’s cabinet representation and legal gender equality when the level of democracy is higher and when legislative power is higher.

Institutional variables: To test hypothesis two, the authors include two institutional variables in the dataset. The first is Democracy, a measure of electoral democracy as coded by V-Dem. In electoral democracies, there is electoral competition including for the position of the country’s leader, universal suffrage, free and fair elections, and civil liberties. Second, following Kim (2022), the authors created Legislative power, which codes the legislature’s lawmaking power using six V-Dem variables. The variables assess whether the legislature has control over its own resources, can introduce bills, and needs to approve bills before bills can become legislation; the degree to which the legislature has a functioning committee system; whether every member of the legislature has a policy expert as a staff member; and the percentage of members of the legislature who are directly elected. The authors standardized each of the six variables and then calculated the average to create Legislative powers.

To compare the relationships for countries with low and high levels of democracy and low and high levels of legislative power, the authors categorized the countries into low and high. The study considers the full time period for which data are available, and therefore categorizes countries based on the mean level of democracy and mean level of legislative power across 1970-2022. Countries whose mean level of democracy falls below the sample’s median democracy level in 201995 are categorized as low. Countries whose mean level of democracy is higher than the sample median in 2019 are grouped as high. In the low legislative power category, countries’ mean legislative power scores fall under the sample’s median score in 2019. Countries with a mean legislative power score that exceed the sample’s median in 2019 are categorized as high.

Robustness checks: To control for a potential confounder, the authors included a country’s level of economic development. GDP per capita (ln) is the natural log of real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in 2011 USD, adjusted for purchasing power parity. The authors’ main source of information on GDP is the Maddison Project Database.96 To include as many countries as possible in the study, the authors impute logged GDP per capita for observations that are missing in the Maddison Project Database.97

Country fixed effects: Consistent with Kim (2022), the authors use country fixed effects regression models to test whether there is a relationship between changes in the percentage of women in the legislature and in the cabinet and changes in the WBL 1.0 index. This allows the authors to account for country-specific factors that do not vary over time (such as former colonial power, geography). In all the models, the authors include a linear time trend (that is, year) to address the fact that the WBL index and women’s representation are generally increasing across the sample period.

Time lag: Finally, to account for the length of time it may take for bills to become legislation, the authors lag legislative and cabinet representation by three years.98 For the control variables, the authors lag them by one year.

“Effective power scale” for the head of government and head of state: Two variables were created for the purpose of this Representation Matters report to assess whether the position of the head of state and the head of government in a country has the effective power to lead. The variables are coded only for 2023 and are scaled 0 = ceremonial power and 1 = effective power.

For the head of government, it is coded as:

1 if the head of government has power to appoint and dismiss cabinet ministers (v2ex_hogw = 1 or .5); and 0 if the head of government has no power to appoint and dismiss cabinet ministers (v2ex_hogw = 0). That is missing if the head of state and government are the same person or due to missing data.99, 100

For the head of state it is coded as: